How I play music by ear

People often ask me how I can play a song by ear, without referring to a chord-over-lyrics chart or a sheet music1. I will try to explain it in this note.

My guess is that people kinda assume that when I hear a song, I hear the exact notes and chords, and can play back what I hear. Let’s say I listen to Fly Me to the Moon, you might think this is what I hear:

However, that is not what happens.

First, knowing exactly which notes make up the chord requires perfect pitch, which I don’t have. And it’s impossible to develop perfect pitch after 6 years old.

Even if one has perfect pitch, there are so many chords one needs to recognize. There is a set of chords, called the “major scale diatonic chords.” These are the most basic chords commonly used in pop music. That set alone has 40 distinct chords: C, Cm, C#, C#m, C#dim, Db, D, Dm, Ddim, D#m, D#dim, Eb, E, Em, Edim, E#m, E#dim, F, Fm, F#, F#m, F#dim, G, Gm, Gdim, G#, G#m, G#dim, Ab, A, Am, Adim, A#m, A#dim, Bb, Bbm, B, Bm, Bdim, B#dim.

When I listen to music, this is what I hear:2

Disclaimer

I am not a formally trained musician, and I don’t play professionally. I just enjoy playing music and I’m writing this note based on my own perspective because many people asked me how I do it.

Same song, many versions

If you search for the chords of Fly Me to the Moon, you will find that there are many versions, and some versions has different chords than the others.

Even though the chords are wildly different, when you play them on the instrument, they all feel the same, just that some sound higher-pitched and some sound lower-pitched.

It seems like there’s some underlying simpler system that produced these set of chords.

…and that’s one problem of chord-over-lyrics charts: It shows what chords to play on an instrument, but it doesn’t show the underlying simpler system that produced that chord.

Abstract chords

Abstract chords represent the underlying harmonic structure of a song. These chords are abstract because you can’t directly play them on an instrument, until you put them in a key. (In other words, they are key-independent.)

Putting these abstract chords in different keys indeed produces the different versions you see on the chord-over-lyrics charts.

These green notations you see (6m, 2m, 5, and 1) are one way to represent these abstract chords. They are called the Nashville Number System, which is designed to be easy to learn for untrained musicians like me.

(There are other, more popular ways, to represent these abstract chords, such as the notation used in Roman numeral analysis, which is more popular with formally trained musicians. In Roman numeral analysis, 6m–2m–5–1 is known as the vi–ii–V–I progression.)

Some extra pedantic notes

The Nashville Number System and Roman numeral analysis not only differ in the notation; they also seem to differ in how they think about keys.

In Nashville Number System, we tend to only think in the major scale. A song in the key of E minor is thought of as a song in the key of G major — and we just say it’s in “key G.”

This system is simpler — remember the 40 major scale diatonic chords? When you make them key-independent, you are left with just 7 abstract chords: 1, 2m, 3m, 4, 5, 6m, and 7dim.

Table of major scale diatonic chords in all 12 keys

| Key | 1 | 2m | 3m | 4 | 5 | 6m | 7dim |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | C | Dm | Em | F | G | Am | Bdim |

| G | G | Am | Bm | C | D | Em | F#dim |

| D | D | Em | F#m | G | A | Bm | C#dim |

| A | A | Bm | C#m | D | E | F#m | G#dim |

| E | E | F#m | G#m | A | B | C#m | D#dim |

| B | B | C#m | D#m | E | F# | G#m | A#dim |

| F# | F# | G#m | A#m | B | C# | D#m | E#dim |

| C# | C# | D#m | E#m | F# | G# | A#m | B#dim |

| Ab | Ab | Bbm | Cm | Db | Eb | Fm | Gdim |

| Eb | Eb | Fm | Gm | Ab | Bb | Cm | Ddim |

| Bb | Bb | Cm | Dm | Eb | F | Gm | Adim |

| F | F | Gm | Am | Bb | C | Dm | Edim |

Each abstract chord has a unique personality. I really recommend watching Louie Zong’s chord personalities video. It also exposes you to common chords other than the major scale diatonic chords, such as 3, 2, 4m, b6 and b7. Note that the video uses the Roman numeral analysis notation.

As these abstract chords are key dependent, you don’t need perfect pitch to “feel” the personality of these chords. That is, once you train yourself to recognize the 6m abstract chord, you will hear it in a song in any key. This is a “relative pitch” skill, and there are many apps that can help you train this skill.

Also note that there are a lot of duplicate chords in the table above. Chords don’t mean much without the context (the key it is in). For example, the C chord in the key of C sounds ‘resolved’ or ‘at home’, while the same C chord in the key of F sounds ‘tense’ or ‘unresolved’. Meanwhile, the 1 chord will sound at home regardless of the key it is in.

Scale degrees for melodies

The same goes for melodies:

The notation you see is based on the tonic sol-fa system, which is a system to represent melodies in a key-independent way.

There are seven basic scale degrees to recognize — d, r, m, f, s, l, t — and they are pronounced or sung as “do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti.” The d (the first scale degree, also called the tonic) corresponds to the song’s key. That is, if the song is in the key of Ab, then d corresponds to Ab.

Table of scale degrees and their corresponding pitch classes in all 12 keys

| Key | d | r | m | f | s | l | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

| G | G | A | B | C | D | E | F# |

| D | D | E | F# | G | A | B | C# |

| A | A | B | C# | D | E | F# | G# |

| E | E | F# | G# | A | B | C# | D# |

| B | B | C# | D# | E | F# | G# | A# |

| F# | F# | G# | A# | B | C# | D# | E# |

| C# | C# | D# | E# | F# | G# | A# | B# |

| Ab | Ab | Bb | C | Db | Eb | F | G |

| Eb | Eb | F | G | Ab | Bb | C | D |

| Bb | Bb | C | D | Eb | F | G | A |

| F | F | G | A | Bb | C | D | E |

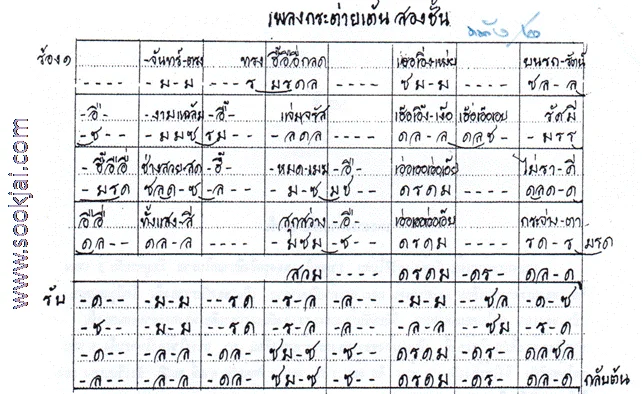

If you are a Thai person, this may be familiar, because traditional Thai music uses a variation of the tonic sol-fa system to notate melodies (example), in which notes are named ด, ร, ม, ฟ, ซ, ล, ท. I learned traditional Thai music in elementary school (it is part of the curriculum), and we are taught to learn to sing the notes first, before playing it on the instrument (it helps with remembering the song and also contributed to my relative pitch skills).

The scale degrees can also be written as numbers, sometimes with a caret (^) on top: 1̂, 2̂, 3̂, 4̂, 5̂, 6̂, 7̂.

(In addition, these scale degrees can be raised (sharpened) or lowered (flattened) by a semitone to make the melody fit the chords better, or to produce spicier or more exotic sounds, but that’s some more advanced stuff that we’ll not get into in this note.)

Movable-Do

If you studied some music, you may be taught that Do–Re–Mi–Fa–Sol–La–Ti corresponds to the notes C–D–E–F–G–A–B respectively. This is true in the fixed-do system. Piano lessons usually teach this system as it helps with sight-reading sheet music.

The tonic sol-fa system is instead based on the movable-do system, where Do–Re–Mi–Fa–Sol–La–Ti corresponds to the scale degrees.

The “Do-Re-Mi” Song from The Sound of Music is a great song to learn movable-do. In this song, the words Doe–Ray–Me–Far–Saw–La–Tea corresponds to Bb–C–D–Eb–F–G–A respectively. The song is in the key of Bb. The longer version of this song has more complex exercises. As the song puts it: “When you know the notes to sing, you can sing most anything.”

Figuring out the key

With relative pitch, you will be able to recognize the abstract chords and scale degrees in a song. But to actually play the song on an instrument, you need to decide which key to play it in. If you play with other people, you need to agree on the same key.

I don’t have a way to explain this in a concise and easy-to-understand way, but it comes naturally with practice and this is what I usually do:

- Ask a bandmate what key the song is in.

- Sing the d into a tuner app and let it tell me the key.

- Play a random note on the instrument until I find the d. (With enough practice, one can do this in a way that people don’t notice.)

Playing the song in that key

Once the key is known, the abstract chords and scale degrees can be converted to chords and notes, and then played on an instrument. There are 2 ways to do this:

Learn to play in one key (e.g. key C) and use the instrument’s transpose function to automatically transpose the performance to the desired key. This is what I do most of the time, but there are a few major drawbacks:

- If the there’s a mid-song key change, I have to change the transpose setting on the fly. This can disrupt the flow of the performance.

- This is only possible if the instrument you’re playing has a transpose function. Not all instruments have this function.

Learn to play in all 12 keys. This is arguably much harder, but it gives you a lot of flexibility.

Use an isomorphic keyboard, where the same chord shape are played the same way in all keys. I played around with it a bit but I don’t think it’s for me.

Footnotes

Although I can read a chord chart or sheet music a little bit, I am very bad at sight-reading. If you give me one and ask me to play it, I probably can't. But if you have me listen to a song a few times, I probably can play it back. ↩

I hear both the melodies and the chords in a similar fashion, but in this note, I will just focus on the chords. ↩